Venture Clienting: A scientific insight

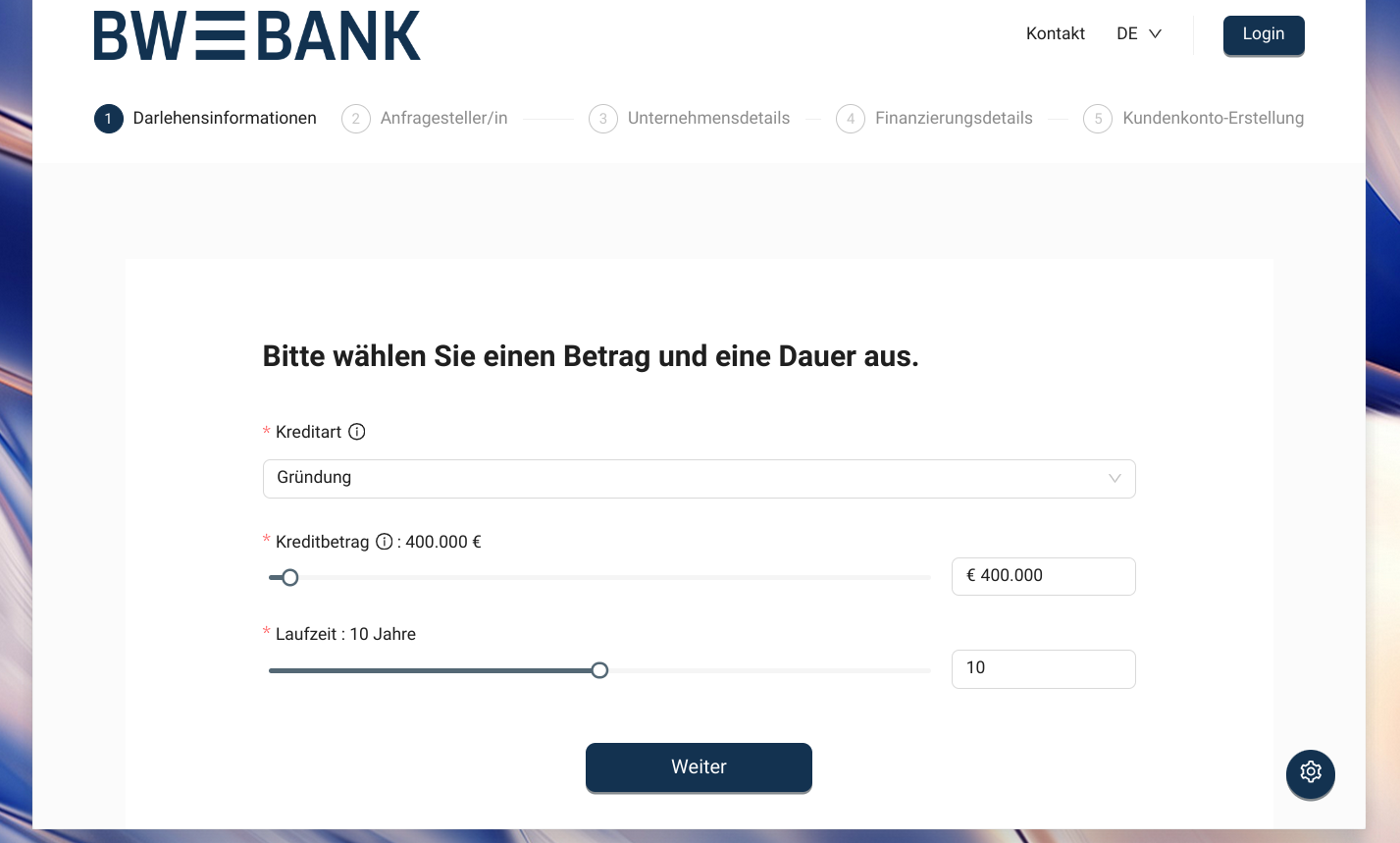

This article appears in the Venture Clienting theme world powered by LBBW. As a medium-sized universal bank with its own venture clienting model, LBBW works specifically with start-ups to transfer innovative technologies into banking practice. The scientific perspective of this article complements this practice and classifies how structured startup cooperations can create added value.

Executive Summary

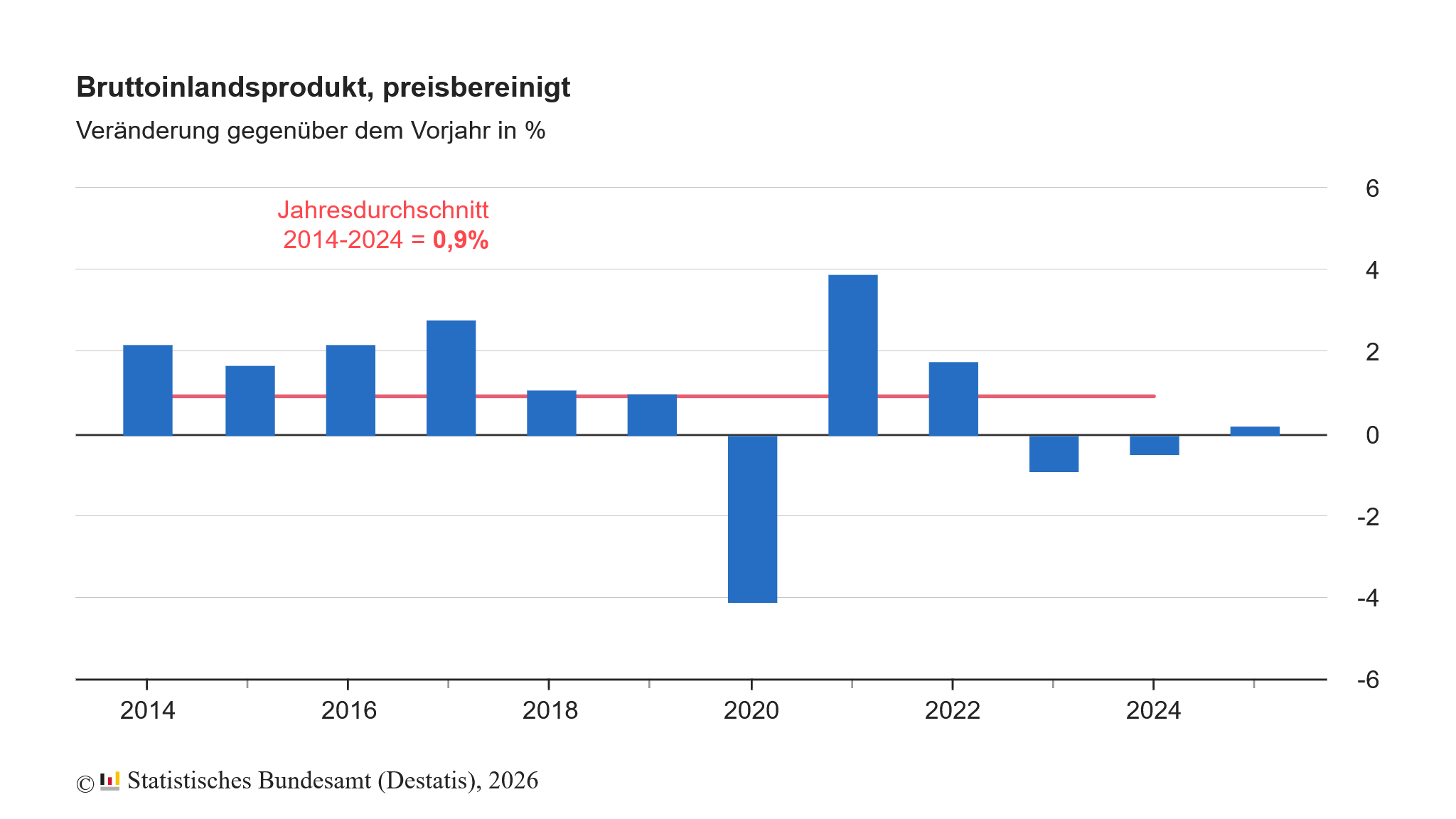

Startups have long since become key partners in the innovation system of established companies. But how can their speed, creativity and proximity to solutions really be effectively translated into corporate structures? Venture clienting - the systematic use of startup solutions through commercial piloting and implementation instead of capital investment - promises exactly that. The approach has gained considerable visibility in recent years and is increasingly being anchored as an independent category in the corporate venturing toolbox.

This article offers a brief scientific classification of the phenomenon: it highlights scientific literature strands in which it is discussed. At the same time, it shows why the actual innovation lies less in the systematics than in the semantic visualization of an existing pattern. Venture clienting is therefore not just an operational tool, but an expression of a modern innovation logic: targeted, needs-oriented and connectable to real business practice.

1 Introduction

Innovation no longer takes place exclusively behind closed company doors. Ever since the publication of the book "Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting From Technology" (Chesbrough, 2003) in 2003 by the recently retired Berkeley professor Henry Chesbrough, who coined the term of the same name, it has been clear that in an increasingly networked world, it is becoming a strategic necessity for companies to systematically integrate external ideas, technologies and talents into their innovation processes.

This is precisely where the concept of venture clienting comes in - a model that is still relatively new, but has received a lot of attention in practice. It describes companies that do not finance promising technologies from start-ups, but acquire them as their first customers, use them and integrate them into their structures in order to realize targeted innovation impulses and secure competitive advantages.

The approach was primarily popularized by BMW (Gimmy et al., 2017) and has since made it into the Gartner Hype Cycle for Innovation Practices (Gartner, 2024) - an indicator of its growing prevalence and increased interest in industry and the consulting world. However, while the first implementation models are emerging in practice, the scientific debate is still in its infancy. However, it is precisely this bridging of the gap - between operational reality and theoretical foundation - that is crucial to understanding venture clienting as a robust innovation architecture in the long term (Gutmann et al., 2024)

2 What we know about venture clienting - a look at the research

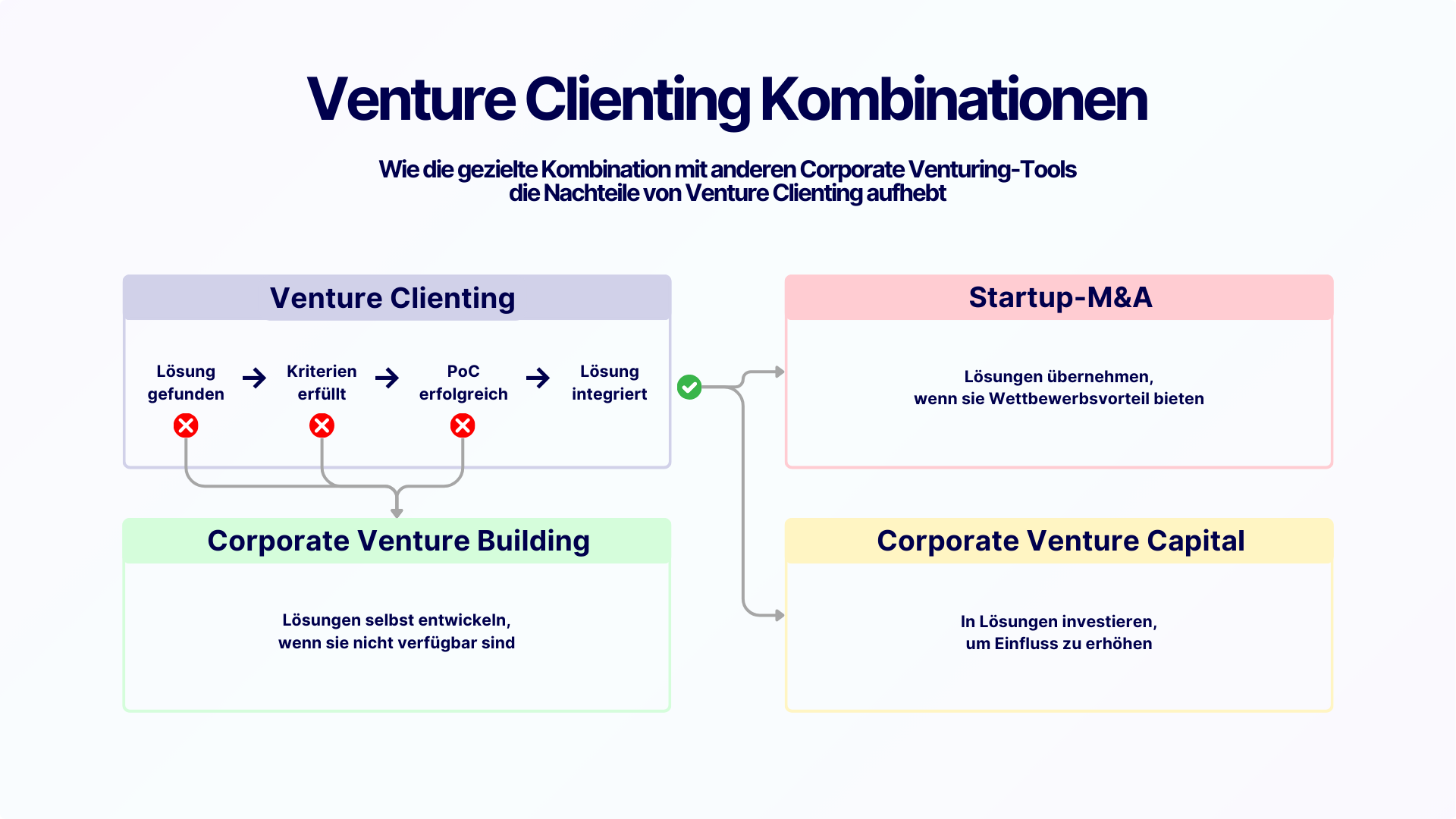

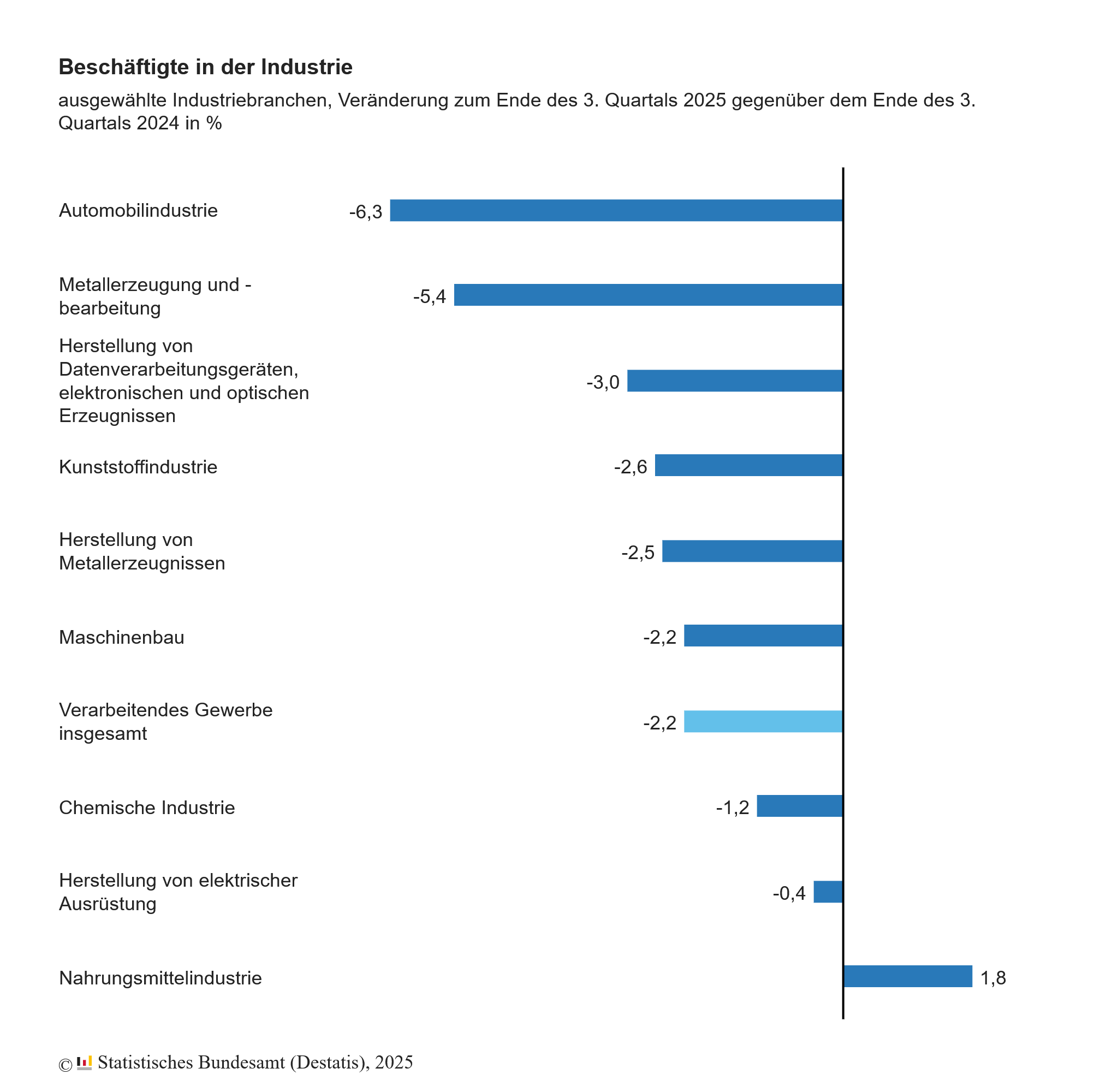

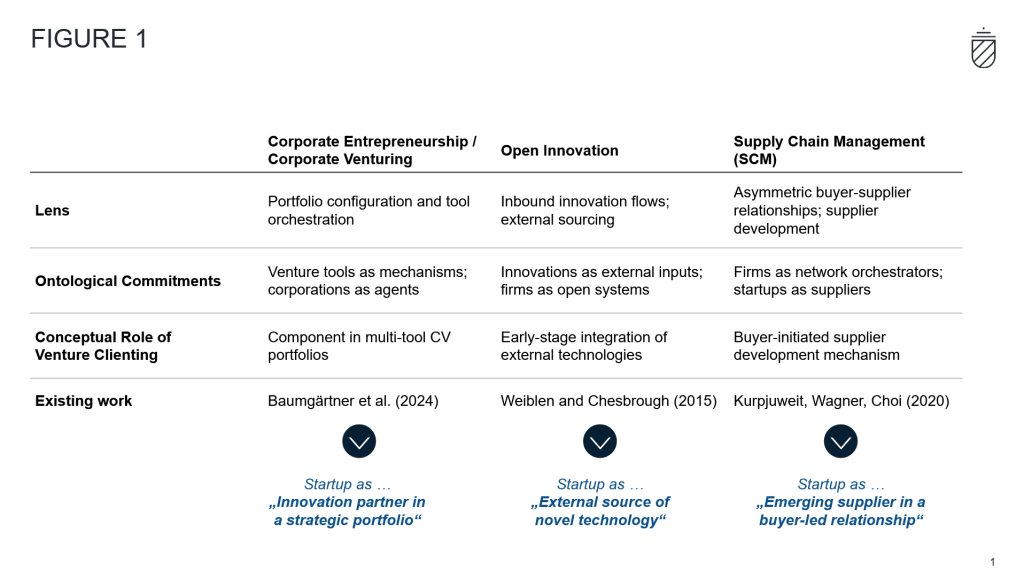

Despite its increasing importance in corporate practice, venture clienting is still a young and conceptually fragmented field in academic research. There have been few dedicated studies to date, but important theoretical anchors can be derived from selected strands of research that help to systematically capture and understand the phenomenon. Three central perspectives have emerged in the research literature to date: Corporate Venturing, Open Innovation, and Supplier Development in the context of supply chain management (see Figure 1).

2.1 Corporate venturing: venture clienting as an operational bridging mechanism

The term corporate venturing encompasses far more than just corporate venture capital (CVC). In research, it is understood as a generic term for all organizational activities with which established companies promote entrepreneurial behavior - internally (e.g. through incubators) or externally (e.g. through startup collaborations) (Burgelman, 1983; Covin & Miles, 1999). Venture clienting can be categorized in this extended corporate venturing concept: as a non-investment but strategic instrument for integrating external technologies into existing business processes.

In contrast to CVC, where capital commitment and strategic learning go hand in hand, venture clienting is aimed at fast, low-risk solution partnerships with start-ups - typically in the context of specific needs (Baumgärtner et al., 2024). It is not about building a startup portfolio in the financial sense, but about the curated adoption of entrepreneurial solutions, embedded in a strategic search and piloting regime.

Weiblen and Chesbrough (2015) refer to this as "access to innovation without ownership". Here, companies act as clients with a strategic interest, not as shareholders. Venture clienting thus functions as a complementary mechanism in multi-tool venturing portfolios that combines operational proximity and technological exploration - without an investment logic, but with a clear value contribution to the strategic innovation agenda.

2.2 Open innovation: venture clienting as a structured inbound channel

The concept of open innovation (Chesbrough, 2003; 2006) postulates that companies become more innovative and adaptive by opening up their innovation processes in a targeted manner - i.e. by integrating external sources. Dahlander and Gann (2010) distinguish between four modes: inbound vs. outbound and pecuniary vs. non-pecuniary. Venture clienting clearly falls into the inbound-pecuniary mode: companies pay for external knowledge in the form of functioning solutions.

This is not about generating ideas with the crowd, but about the systematic identification, validation and implementation of start-up technologies that can solve specific problems in the company. Venture clienting thus offers a structured answer to the classic problem of local search bias (Laursen & Salter, 2006): Companies often only search in known technology fields - startups, on the other hand, operate on the fringes where new solutions emerge.

However, the real value is only created through internal connectivity: without suitable processes, stakeholder engagement and implementation architecture, the external impetus fizzles out. Venture Clientingo perationalizes the principle of open innovation with startups along concrete processes, budgets and governance models.

2.3 Supply chain management: startups as strategic early suppliers

Research on supply chain management also provides valuable perspectives on venture clienting - particularly in the area of supplier development and asymmetrical buyer-supplier relationships. Kurpjuweit, Wagner and Choi (2020) explicitly examine how early-stage startups can be positioned as potential suppliers for large companies - despite their structural weaknesses (e.g. low scalability, lack of quality systems).

In this logic, venture clienting functions as an instrumentalized maturity model: start-ups undergo an accelerated "qualification process" in order to make their solution operationally compatible. The Group not only assumes the role of customer, but also that of co-developer, risk manager and scaling enabler - often without formal standard supplier registration or long-term purchase guarantees.

This positioning of the start-up as an "emerging supplier in a buyer-led relationship" is key to understanding the dynamics: Venture clienting is (at least in the first step) not a partnership-based co-creation model, but a targeted, problem-oriented procurement under uncertainty, in which selective integration and early feedback play central roles.

Unlike traditional procurement models, however, venture clienting is not (only) geared towards efficiency, but (also) towards learning and exploration. It thus combines the principles of supply chain management with the goals of strategic early innovation - and enables new forms of supplier relationships under highly dynamic conditions.

3 What characterizes successful venture client models - and why they fail

Venture clienting promises a lot: access to disruptive technologies, faster innovation cycles and strategic capability sourcing - without tying up capital. However, success does not depend solely on the quality of the start-ups. Rather, it is internal structures, processes and cultural connectivity that make the difference between effectiveness and ineffectiveness.

3.1 Success factor #1: Clear problem pull instead of technology-driven push

An important success factor is a clearly articulated need from the operational business. Venture clienting is successful when it addresses real problems - not when it "somehow" brings exciting start-ups into the company. Experience shows that push-driven models in which start-ups are pitched without a concrete use case are often met with rejection or disinterest.

Successful venture client units therefore work with need owners, i.e. internal departments that have a problem - and are therefore intrinsically motivated to test and implement an external solution. In this context, the literature speaks of "solution pull", which promises a significantly higher adoption success rate.

3.2 Success factor #2: Structured processes - the WFGM model as a blueprint

Many companies develop their venture client processes along stage-gate or phase models. In practice, there are very different variants - from three to around seven steps - supplemented by labels such as Identify, Discover, Assess, Evaluate, Buy, Purchase, Proof-of-Value, Proof-of-Concept, Pilot, Test, Implement, Scale or Adopt. Despite this diversity, all models are ultimately based on the same tried-and-tested standard phases that are familiar from "classic innovation management".

An established reference model is the Want-Find-Get-Manage (WFGM) framework by Slowinski (2010). It summarizes the entire process from clarifying requirements to post-pilot integration in four clear steps:

- Want: Clarify and strategically define internal needs

- Find: Identify and evaluate suitable start-ups

- Get: Set up contracts, check risks and determine resources

- Manage: Support pilot, evaluate results and scale solutions

The comparison makes it clear that whether a company uses three, five or seven phases - and how they are labeled - does little to change the basic system. It has proven itself in innovation management over decades and remains a central building block for process excellence today. It is precisely this clear structure that makes it possible to move efficiently from the identified need to the appropriate solution.

In successful organizations, these phases are not just a checklist, but are embedded in interlinked governance, reporting and decision-making systems - often with dedicated teams, clear roles (e.g. "startup owner"), evaluation frameworks and standardized pilot specifications. Dedicated software that manages this process at least in the innovation team, or ideally even company-wide, can support the scaling of collaboration activities.

3.3 Success factor #3: Internal connectivity and implementation expertise

Even the best start-up solution is ineffective if it is not implemented operationally. Many venture client projects fail not because of the proof of concept, but because of the transfer to operations - for example due to a lack of resources in the specialist area, IT hurdles, data protection concerns or a lack of internal sponsors.

This is why venture clienting must be geared towards internal integration from the outset. Successful units invest heavily in change management, interface management and executive buy-in. In some cases, venture clienting is also institutionalized as part of the procurement strategy (e.g. "emerging supplier readiness") - particularly in the case of industrial giants with complex quality assurance processes.

- Success factor #4: Clear governance, KPIs and strategic anchoring

The question of where venture clienting is organizationally anchored influences its impact. Whether a unit is organized centrally (e.g. in the CTO or digital area) or in a network with local champions (e.g. across business units with venture client leads per area) has an impact on the approach. In both cases, it is clear that venture clienting needs to be doubly anchored - strategically and operationally. This includes

- Governance models with defined decision-making processes

- KPIs, e.g. time-to-adoption, cost-per-pilot, implementation ratio

- Reporting lines, e.g. to C-Level or Innovation Board

These structures ensure legitimacy, visibility and impact - and also show that there is no "one-size-fits-all" for such units, but that the context, experience, culture and skills of a company influence the right setting.

3.5 Why some models fail - typical stumbling blocks

Research and practical reports show recurring sources of error:

- Innovation theater: startups are invited but not seriously piloted, implemented and scaled.

- Lack of internal demand: VCLUs work without a clear need from the business

- Isolation: Venture clienting is operated as an "innovation sidecar" without a connection to core processes

- Excessive demands: start-ups are forced into pilot structures that do not correspond to their maturity

These points make it clear: Venture clienting is not a sure-fire success. It needs strategic clarity, internal maturity and systematic management in order to develop its full potential.

4 Where is venture clienting heading?

Venture clienting is at an exciting point in its development: while in the early phase it primarily served as a pragmatic procurement tool for startup technology, it is increasingly developing into a strategic orchestration model - with links to platform logics, ecosystem management and digitalized innovation infrastructures. Three lines of development are emerging particularly clearly: platformization, automation through artificial intelligence and integration into strategic innovation management.

4.1 Platformization: from pilot project to systemic orchestration

More and more companies are linking venture clienting to company-wide platform architectures in which requirements, scouting processes and startup relationships are managed digitally. In some industries, venture collaboration platforms are emerging that enable companies to structure and automatically match both internal requirements and external solutions. Venture clienting is thus becoming an orchestration tool for innovation ecosystems - and is increasingly acting as an "innovation-as-a-service" structure for specialist departments.

4.2 Artificial intelligence and automated matching

With the introduction of generative AI models, and above all agentic AI, into the innovation process, the role of venture clienting is also changing. The first providers are working on AI-supported matching systems that automatically classify problems, identify suitable start-ups and make an initial pre-selection - based on semantic analysis of pitch decks, websites and tech profiles, for example.

In the future, venture client units could act more as "AI-assisted innovation brokers": They orchestrate the flow of innovation, while repetitive tasks such as scouting, due diligence light or fit-gap analyses are increasingly supported by algorithms.

This development opens up new fields of research:

- What biases are created by AI-supported startup matching?

- How are decision-making patterns changing in the pilot allocation process?

- What skills will the venture client unit of the future need?

4.3 Integration into strategic innovation management

While venture clienting is often seen as an operational unit today, initial developments are emerging to embed the model in strategic innovation management. Companies are experimenting with models in which venture clienting is directly linked to strategy processes and roadmapping .

This development is particularly relevant to the question of "strategic fit": instead of piloting selective solutions, companies are evaluating how startup technologies can specifically contribute to strategic capability gaps - for example in terms of sustainability, digital transformation or new value creation models.

Research questions that arise from this:

- How can "capability fit" between startup and corporation be systematically evaluated?

- Which governance models ensure strategic coupling with operational flexibility?

- How does venture clienting change the understanding of the role of corporate innovation?

5 Conclusion: From newcomer to strategic innovation driver

Venture clienting is more than just a new fashion trend in the corporate innovation toolbox. It is an attempt to answer a structural dilemma: how can established companies succeed in translating the speed, creativity and solution-oriented approach of start-ups into their own organization - beyond investments, shareholdings or pure innovation symbolism?

The term Venture Clienting was first prominently coined by the BMW Startup Garage in an article in the Harvard Business Review. In retrospect, this deliberate naming - pointed, easy to remember and strategically positioned - was not only an act of innovation in terms of content, but also semantics. Even though the principle of "startups as solution providers" was by no means new, there was no clearly defined label that made this practice visible as an independent model.

Long before the term was coined by BMW, companies were already working systematically with startups: for example, as part of technology sourcing processes, incubator-related procurement experiments or pilot projects with corporate procurement integration. Venture clienting now gives this practice a name, a structure - and therefore strategic legitimacy. To put it bluntly, it is a semantic professionalization of an existing pattern of action.

This semantic framing is also more than cosmetic: in practice, it means that venture clienting is increasingly seen as an independent category within corporate venturing portfolios - alongside corporate venture capital, accelerators, incubators or startup labs. The growing number of dedicated venture client units, toolkits, scouting platforms and governance standards is evidence of this: The model is professionalizing and maturing.

At the same time, it is becoming clear that the real challenge lies not in the naming, but in the operational implementation. Companies that want to successfully establish venture clienting need

- strategic clarity about the target image and use cases,

- internal processes for identifying, evaluating and adopting solutions,

- and a culture that combines openness with implementation strength.

Venture clienting will not replace all other forms of startup collaboration in the coming years - but it will play an increasingly important role as a bridging model: between rapid testing and strategic scaling, between explorative access to innovation and operational impact. It is therefore not just a new name - but an important piece of the mosaic in the restructuring of large companies' innovation architectures.

References

Baumgärtner, L. D., Stoffregen, R., Soluk, J., Kammerlander, N., & Gimmy, G. (2024). Harnessing the innovative potential of start-ups for corporate entrepreneurship in incumbent firms: A study of asymmetric buyer-supplier relationships. R&D Management. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/radm.12726

Burgelman, R. A. (1983). A process model of internal corporate venturing in the diversified major firm. Administrative Science Quarterly, 28(2), 223-244. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392619

Chesbrough, H. (2003). Open innovation: The new imperative for creating and profiting from technology. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Chesbrough, H. W. (2006). Open business models: How to thrive in the new innovation landscape. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Covin, J. G., & Miles, M. P. (1999). Corporate entrepreneurship and the pursuit of competitive advantage. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23(3), 47-63. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879902300304

Dahlander, L., & Gann, D. M. (2010). How open is innovation? Research Policy, 39(6), 699-709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2010.01.013

Gartner, Inc (2024). Hype cycle for innovation practices, 2024. Retrieved from https://www.gartner.com/en/documents/5563795

Gimmy, G., Kanbach, D. K., Stubner, S., König, A., & Enders, A. (2017). What BMW's corporate VC offers that regular investors can't. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2017/07/what-bmws-corporate-vc-offers-that-regular-investors-cant

Gutmann, T., Greiss, S., & Hüttenhein, C. (2024). Venture clienting: How to partner with startups to create value. London: Kogan Page.

Kurpjuweit, S., Wagner, S. M., & Choi, T. Y. (2021). Selecting startups as suppliers: A typology of supplier selection archetypes. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 57(3), 25-49.

Laursen, K., & Salter, A. (2006). Open for innovation: The role of openness in explaining innovation performance among U.K. manufacturing firms. Strategic Management Journal, 27(2), 131-150. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.507

Slowinski, G., & Sagal, M. W. (2010). Good practices in open innovation. Research-Technology Management, 53(5), 38-45. https://doi.org/10.1080/08956308.2010.11657649

Weiblen, T., & Chesbrough, H. W. (2015). Engaging with startups to enhance corporate innovation. California Management Review, 57(2), 66-90. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2015.57.2.66

More about this

Venture Clienting

Newsletter

Startups, stories and stats from the German startup ecosystem straight to your inbox. Subscribe with 2 clicks. Noice.

LinkedIn ConnectFYI: English edition available

Hello my friend, have you been stranded on the German edition of Startbase? At least your browser tells us, that you do not speak German - so maybe you would like to switch to the English edition instead?

FYI: Deutsche Edition verfügbar

Hallo mein Freund, du befindest dich auf der Englischen Edition der Startbase und laut deinem Browser sprichst du eigentlich auch Deutsch. Magst du die Sprache wechseln?