How start-ups also fall into the greenwashing trap

Not only the really big companies, but also start-ups lure customers with false promises of sustainability, as some prominent cases show. But the courage to be honest pays off.

Fintech Tomorrow promises its around 124,000 customers a climate-neutral account. Unlike commercial banks - which have attracted attention in the past for investing in coal-fired power companies, for example - Tomorrow is committed to "sustainability and social justice". For example, by investing customer deposits sustainably.

However, a look at the app shows that only around 30 percent of the approximately 369 million euros in deposits have been invested so far. This means that around 70 percent of the money is "impact-free" at the Bundesbank.

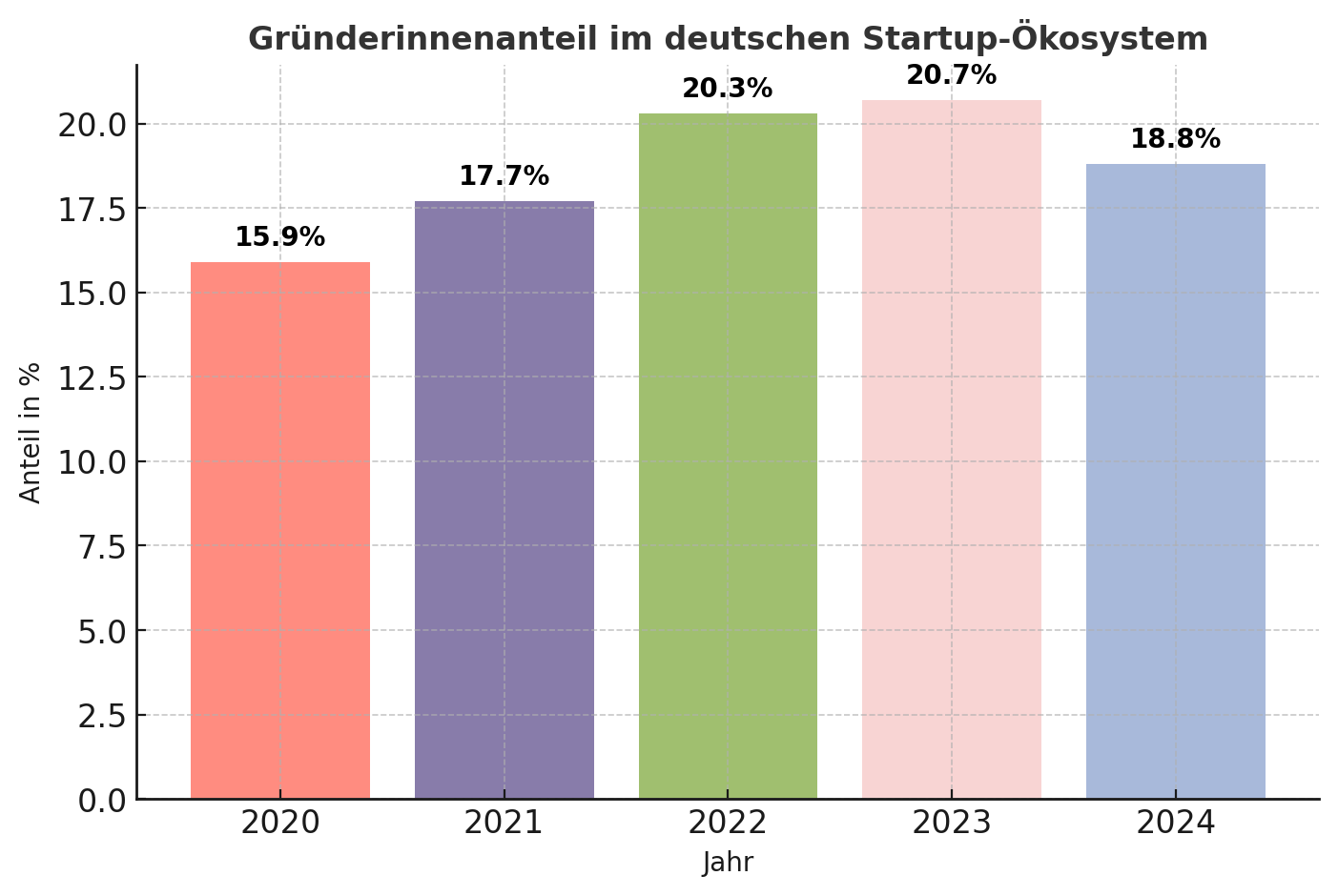

Not just starting up, but making the world a better place. More than three quarters of all founders in Germany want to achieve a positive social or ecological impact with their start-ups, according to figures from the Green Startup Monitor. But sometimes start-ups run behind their own good intentions, just like Tomorrow. It is difficult to find suitable financial investments, said Tomorrow founder Jakob Berndt in the 2021 Finance Forward podcast.

The fact that a fintech advertises impact investments on the one hand, but 70 percent of deposits are "impact-free" on the other, is a form of overcommunication that is not unique. "Sustainability is a reason to buy for more and more consumers and therefore an important advertising argument for companies," explains green marketing expert Reinhard Herok, who conducts research at the Institute for Sustainability at the Wiener Neustadt University of Applied Sciences. In their zeal, companies often tend to overdo it when it comes to green marketing. A classic example is the communication of self-evident facts, such as "CFC-free", even though these greenhouse gases have long been banned anyway. This form of marketing is greenwashing.

Consumers usually associate the word "greenwashing" with advertising campaigns by large companies whose business has a proven negative impact on the environment: large clothing companies that suddenly advertise with eco-cotton and do not stop launching new fashion collections every two weeks, thus promoting overconsumption. This also includes airlines that offer their customers to pay a little more to offset the CO2 emitted on their flight.

Start-ups also tend to greenwash

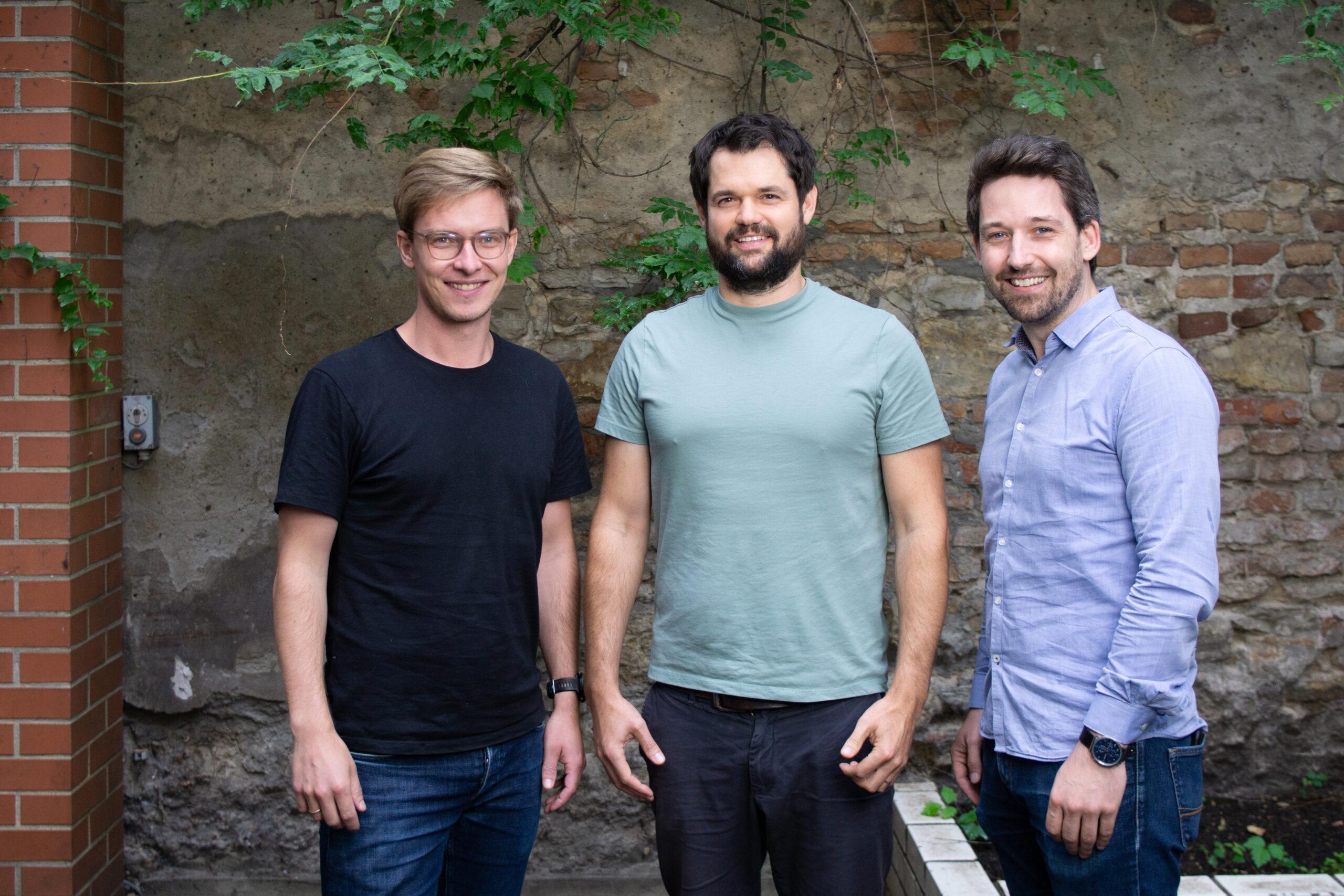

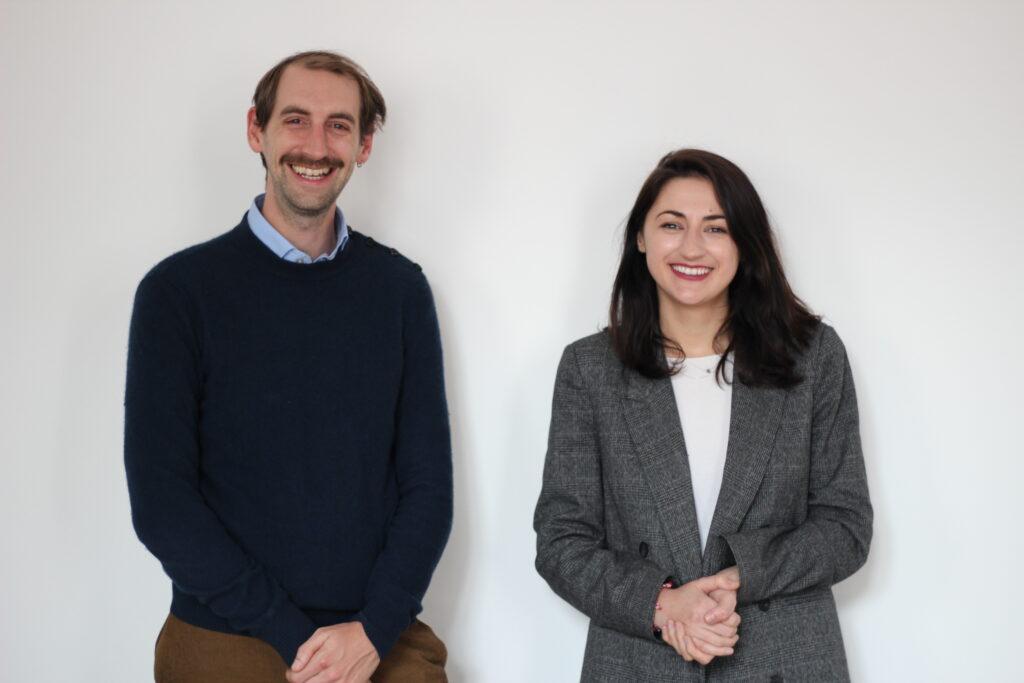

But start-ups also tend to fall into the greenwashing trap - often not with bad intentions, as Nathan Bonnisseau explains. He founded Plan A and developed carbon accounting software to help companies measure and reduce their emissions. "There are many companies that want to do everything right but have no expertise in the field." A common consequence: they advertise with vague sustainability promises that have not yet been substantiated anywhere.

This has also happened to the green fintech Tomorrow: In the past, the banking app provider advertised its premium account with the promise that the account holder could use it to offset their own carbon footprint. The Baden-Württemberg consumer advice center therefore issued Tomorrow with a warning for misleading advertising. The argument was that the company was not in a position to know a customer's personal footprint. Tomorrow has since corrected the advertising statement.

"Companies should not advertise with sustainability promises that they cannot fulfill or can only fulfill in the future"

Plan A founder Nathan Bonniseau

"Companies should not advertise with sustainability promises that they cannot fulfill or can only fulfill in the future," advises Bonnisseau. It is better for founders to clearly communicate "which part of their sustainability journey they are on." Because once customers realize that they have been made false promises, it will take a long time for them to regain trust in the company. "When customers find out that a company is doing less for sustainability than it claims, they feel betrayed - and that is a strong emotion."

The example of Air-up shows the ripples that can be caused when a company makes false promises. Together with Der Spiegel, the sustainability portal Flip found out at the beginning of April that the start-up, which offers drinking bottles with scented rings, advertises that it uses significantly less plastic and CO2 emissions. However, according to Flip and Spiegel, there is no life cycle assessment of whether and how much is being saved. Around five months after the article was published, ZDF satirist Jan Böhmermann took up the topic again.

This shows: Once a company has been caught exaggerating about sustainability in its advertising, it takes time for its reputation to recover. And even worse: the entire industry is often affected by such individual cases. "The more greenwashing cases that come to light, the more trust in the private sector declines," says Bonnisseau. This in turn harms the environment, as consumer decisions can certainly influence how sustainably companies operate.

"It's not just customers who are attaching more and more importance to sustainability, but also investors," says green marketing expert Herok. The temptation to advertise with false sustainability promises is high. One popular method: "Companies invent their own seals to make consumers believe they are particularly green."

Seals are sometimes awarded without verification

It is becoming increasingly difficult for consumers to see through this - especially as there are also providers who award labels without requesting proof of CO2 emissions. This was revealed by an investigation by Die Zeit, which succeeded in obtaining "climate-neutral" labels from three providers for an imaginary start-up. Proof of electricity and heating bills to calculate the CO2 footprint was not requested. The fictitious start-up was also not asked to save CO2 emissions.

Advertising with seals is therefore not necessarily consumer-friendly. But what steps should start-ups that are serious about sustainability take? Bonnisseau advises having emissions measured by experts and then tackling the causes of pollution. "One way to start, for example, is to replace flights with train travel on business trips." Only when a goal has been demonstrably achieved should the start-up advertise it.

Newsletter

Startups, stories and stats from the German startup ecosystem straight to your inbox. Subscribe with 2 clicks. Noice.

LinkedIn ConnectFYI: English edition available

Hello my friend, have you been stranded on the German edition of Startbase? At least your browser tells us, that you do not speak German - so maybe you would like to switch to the English edition instead?

FYI: Deutsche Edition verfügbar

Hallo mein Freund, du befindest dich auf der Englischen Edition der Startbase und laut deinem Browser sprichst du eigentlich auch Deutsch. Magst du die Sprache wechseln?